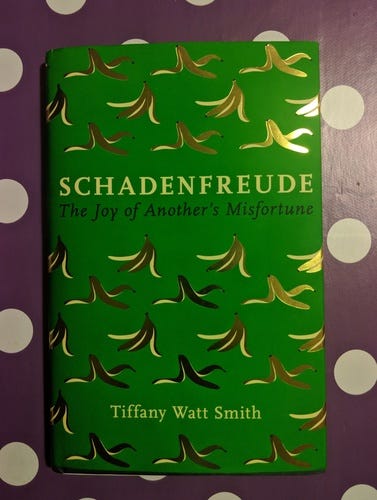

This weekend I was delighted to receive a beautiful copy of Schadenfreude by Tiffany Watt Smith. It has a close connection to my own book The Laughing Baby because Tiffany and I have compared notes as our various projects have progressed. Tiffany is an historian of emotions and the parent of young childen. She has even brought her son to our lab to take part in one of our studies…

You will have to read her book to find out if babies do expeience Schadenfreude. What’s more, Tiffany was one of the first people I interviewed when writing my book. Unfortunately, I didn’t check that sound levels so the recording is essentially inaudible. Nonetheless, her previous book was very helpful when i was trying to answer the following tricky question:

What are emotions?

(From Chapter Nine of The Laughing Baby)

“Emotions do not exist to be locked away inside individuals.”

Vasudevi Reddy and Colwyn Trevarthen, 2004

If laughter evolved as a social glue, central to this role is that it expresses emotion. The most infectious thing about a laughing baby is their absolute delight. It may seem a truism to say that ‘babies laugh because they are happy’. But this challenges us to answer the question what is happiness? While we are about it we might as well try and explain anger, sadness, worry and the rest. It should not surprise anyone that emotions are still mysterious to science. Many theories have been proposed and few have been discarded.

The race for a comprehensive theory of emotion is still wide open. Perhaps, it will always remain so, no scientific theory could catalogue all the nuances of our adult experience. In The Book of Human Emotions, Tiffany Watt Smith describes 156 different emotions. She readily admits this list is not comprehensive and the categories overlap and blur at their edges, changing over time and by culture. Tiffany’s goal as a historian of emotion to offer an argument against the tendency to reduce “the beautiful complexity of our inner lives into just a handful of cardinal emotions” (Watt Smith, 2015).

It is a tendency that has always been there. Tiffany describes the Li Chi, a book from the Confucian era that lists seven essential feelings; joy, anger, sadness, fear, love, dislike and fondness. Two and a half millennia later and little has changed. In the 2015 animated Pixar film Inside Out, the main character, a young girl called Riley, is shown with five emotions; Joy, Anger, Sadness, Fear and Disgust. Modern science usually settles on a list of about nine ‘basic emotions’; happiness, sadness, anger, fear, parental love, child attachment, sexual love, hatred, and disgust (Oatley & Johnson-Laird, 2014). These lists seem reasonable in as far as they go. But the best theories are not about listing emotions but explaining why we have emotions at all.

One of the first people to realise this was Charles Darwin. In a work of visionary genius that often gets overlooked in comparison to his other incredible achievements Darwin advanced one the first ever scientific theories of emotions. His book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (Darwin, 1872a) proposed that our emotions are evolved for our survival. Of course, he would say that wouldn’t he? Like all of Darwin’s work it was supported by decades of patient accumulation of evidence. He compared the anger displays of many animals. He also included many observations of babies. Darwin kept detailed biographical diaries of several of his children and wondered what was meant by their frowns, blushes, and laughs. On a theoretical level Darwin’s account was a bit thin, all it really says is that emotions are universal, valuable and shared with animals. But it was a very radical proposal for its time

About a decade later, William James and Carl Lange each independently decided that emotions were reactions to bodily states. For example, fear might be how we interpreted our racing hearts. For James emotions are literally feelings, “we feel sorry because we cry, … not … we cry … because we are sorry” (p. 180, James 1884). By this view emotions happen after the fact and are what philosophers call ‘epiphenomena’. The theory has been remarkable popular because it suggests that if you carefully measure exactly how a person is reacting physiologically you can tell what emotion they are experiencing. The James-Lang theory feels unsatisfying to me because it relegates emotion to a passive role. But it does have two important strengths. It points out that our physiology strongly influences our mental state and that emotions depend upon interpretation of experience. Contrary to early views of the theory popularised by John Dewey, neither James nor Lang ever insisted on a single emotion for each physiological reaction. They would be quite content that a racing heart and sweaty palms could be interpreted as fear in some situations and as love in others (L. B. Feldman, 2018).

Our old friend Sigmund Freud took a very different view. For Freud, emotions were supremely mental. Our minds are seething cauldrons of desires. Emotions are the main engine that drive us forward or hold us back. Reversing James-Lange theory, Freud even thought that mental turmoil could manifest itself physically as psychosomatic illness. But Freud’s biggest contribution was the invention of the unconscious. He believed our ‘true’ emotions hide from us in our subconscious and they are shaped by momentous events in early life that echo down through our lives. Being unobservable the unconscious is unscientific. Hence my use of the word invention rather than discovery. If you read modern neuroscience papers on emotion, they usually take the trouble to explain why James & Lange were wrong, but do not even bother to mention Freud.

Jaak Panksepp, who we met tickling rats in chapter seven, believes our emotions exist to tell us what supports or detracts from our survival. He thinks we have 7 emotional systems. There are ancient systems of FEAR, RAGE, LUST and SEEKING and more modern mechanisms for CARE, PANIC and PLAY that are unique to social mammals. He capitalises the words to emphasise that he gives them very specific scientific meaning (Panksepp, 2005). Each system serving specific goal and can be mapped to equivalent brain areas in many species. Take the PANIC system which rules babies’ separation anxiety. Panksepp shows that it operates in the brain with the same neurochemistry as physical pain. The pain of separation is real pain and prompts the infant to act, usually calling out to mother in distress. The return of the mother releases opioids and oxytocin which relieve the pain. The brain circuitry goes back to the imprinting in chicks and the survival value is clear in both cases (Herman & Panksepp, 1981).

As well as his laughing rats, Panksepp has looked at sadness in chickens, what makes guinea pigs cry and mother-infant bonding in sheep. He has spent decades researching emotion in animals and is very particular that they feel things in the same way we do. He believes in an emotional consciousness common to humans and animals and cognitive consciousness that comes later with the use of language. Emotions colour our world and the conscious experience of joy or rage is essential to its function for humans and animals alike. It is an unpopular viewpoint. Plenty of scientists are dismissive of the experience of animals. They cite Morgan’s cannon and say science can only ever study animal behaviour. They criticise him because they do not believe animals have consciousness necessary to experience or interpret emotions. In Panksepp’s view, these scientists are looking down the wrong end of the telescope. It is the experience that makes the emotion and experiencing emotions was how and why consciousness evolved. We may have to describe animal emotions with human labels but FEAR came before ‘fear’ and SEEKING before ‘pleasure’. In my view the most case compelling against Panksepp’s critics is that anyone who is dismissive of animal emotions also has dismiss all the emotions of preverbal babies.

Some researchers do argue precisely this position. One forceful critic of Panksepp is Canadian researcher Lisa Barrett Feldman. A professor of psychology at Northeastern University in Boston, she argues that emotions are entirely conceptual and so animals and new born babies cannot have them. Here is what she says about babies

“Babies don’t know what telescopes are, or sea cucumbers or picnics, let alone purely mental concepts like ‘Whimsy’ or ‘Schadenfreude’. A newborn is experientially blind to a great extent.” (p. 113, L. B. Feldman, 2018)

The quote comes from her recent book How Emotions Are Made in which she describes her own theory of constructed emotion. She contrasts this with what she calls classical view of emotions shared by Darwin, Panksepp and others. As I said at the outset of this section, no one theory of emotions covers all the ground yet so it worth looking at things from the opposite perspective. To do this let us go back to Inside Out.

In the film Inside Out, each of the basic emotions is personified as a character inside Riley’s mind. Joy appears first when Riley is a new born baby seeing her blurry parents for the first time. Her job it seems is to press buttons the cause Riley to respond and collect the memories associated with her actions. She is shortly joined by Sadness and the others and each interpret situations and responds according to their nature. Joy delights, Anger gets mad, Fear worries, Disgust dislikes things and Sadness is sad. If we forgive the artistic licence of little people inside your head pressing buttons it is a wonderful depiction of the classical view of emotions. This is to be expected, the main scientific advisor on the film was Paul Ekman who is one of main theorists behind the idea that emotions are universal biological drives (Keltner & Ekman, 2015).

The outer plot revolves around an eleven year old Riley having to adapt as her family move from Minnesota to a new home and new school San Francisco. The inner plot revolves around Joy trying to understand the purpose of Sadness. It is a good film so I won’t spoil it for you but it is not giving too much away to say that the Emotions learn to work as a team and Riley learns that other people struggle with their emotions too. At various points we see into her parents’ heads, their own teams of five emotional essences at their controls. It is a story Barrett claims that would be recognisable to Aristotle, Plato and even the Buddha, but she argues it is built on a myth. Barrett does not believe there are universal emotions. Your emotions are not fixed by evolution but constructed as part of your culture. They do not bubble up from a set of brain areas but are constructed by your highly sophisticated human brain building abstract categories to help classify and your inner and outer lives.

Lisa Feldman Barrett’s theory has no problem with there being hundreds of subtle emotions like those listed in Tiffany Watt-Smith’s Handbook. In fact, Barrett is the editor of her own Handbook of Emotions, an academic volume running to over 900 pages. There can be countless, complex emotions because our highly social lives and big brains create that complexity. But then Ekman and Panksepp do not have any problem with the existence of complex emotions like embarrassment, ennui or exasperation. Where her theory differs is that she does not think happiness, anger or sadness are any more natural or biological than technostress or Torschlusspanik.

But that does not mean that in Barrett’s version of the film there would be 156+ characters all clamouring for attention in Riley’s head. That would be a terrible movie and it would be committing the error of Essentialism. Just because we can classify a set of behaviours as ‘anger’, does not make anger is a real thing. According to Barrett, Plato, Darwin and Panksepp all commit this error. Plato we can forgive. Essences and Platonic Ideals were kind of his ‘thing’. Barrett gives Darwin a particularly hard time and she has a point. His theory evolution removed the need for essentialism from biological classification. But his book on emotions went the other way. Barrett notes that at Darwin says “Even insects express, anger, jealously and love” (p.350, Darwin, 1872).

Why is this an error? Let us take a closer look at Anger. In several chapters of How Emotions Are Made Barrett deconstructs anger to show it is not a single, simple thing. First, she takes aim at Ekman’s famous work supposedly showing that expressions of emotion are universal. But her research shows that neither facial expressions or physiological signals are highly ambiguous. You can be angry without giving any outward sign of it and seems like anger might not be. Second, there is ambiguity in language. ‘Anger’ might mean annoyance, irritation, rage or fury. But some languages Utka Eskimos have no concept of “Anger” while Mandarin has five or more different “Angers”. Some languages would not even recognise our Western notion of emotion. Finally, in Chapter 12 Barrett asks, “Is a Growling Dog Angry”? As you might guess her answer is that “there is no clear evidence that any non-human animals have the sort of emotion concepts that humans do.” (p. 270). Even dogs, who we have been breeding for their loyalty and understanding of us for millennia. The best we can say is that dogs have raw feelings but this is a long way from emotion. Insects, not even that.

It is in how they approach the emotions of babies where gulf between these theories comes into focus. Barrett, for whom emotions are conceptual, spends a lot of time discussing infant pattern recognition abilities and how they learn words and concepts, the mental prerequisites for her cognitive concept of emotions. Panksepp, for whom emotions are feelings, does more to evoke our empathy but usually cannot help reducing things down to biology and brain areas (Panksepp, 2001). It is notable that neither camp engages directly with the experience of the babies themselves. Yet, I think this is precisely where we will find a better sense of what human emotions are and how they build on our animal affect.

Emotion is about more than just classifying feelings, it is about the feelings themselves. A baby may not know that their sadness is “Sadness” or their happiness is “Joy”. But any parent can see that there is something very real contained in their experiences. I am sure that Barrett and Panksepp would both acknowledge this but there does not seem to be much space in their theories for the subjective sense of emotion, its ‘phenomenology’ if you wanted to be fancy. I do not believe a comprehensive theory of emotions exists yet, but such a theory would not be complete if it did not encompass the primal emotional experience of infants.

For more like this, please look out for my book The Laughing Baby. It is being crowdfunded by Unbound Books. Please pre-order your copy or tell your friends with babies.