My talk at TEDx Bratislava, Slovakia, July 2017

Plenty of research has looked at adults’ emotional responses to music. But research with babies is more piecemeal and eclectic, perhaps reflecting the difficulty of asking them what they like. Researchers know that babies can hear and remember music even while they are still in the womb. And one curious study found that newborn babies prefer Bach to Aerosmith.

Most systematic work has found young babies have clear preferences for consonance over dissonance and can remember the tempo and timbre of music they’ve heard before. Babies prefer the female voice but like it even more when it takes on the qualities of “motherese” (the high-energy singsong tone we all naturally adopt when talking to babies). But their emotional responses to music is a bit more of a mystery. What kind of music makes them calm and content? And what makes them happy?

I am an expert on baby laughter and was intrigued when the C&G baby club approached me and music psychologist Lauren Stewart to create “a song scientifically proven to make babies happy” that they could give away to parents. We thought this was an interesting challenge. However, our first proviso was that they shouldn’t use the word “prove”. Our second was that they had let us do real science. They readily agreed.

The first step was to discover what was already known about the sounds and music that might make babies happy. We had some experience. My previous work on the Baby Laughter project had asked parents about the nursery rhymes and silly sounds that appealed to babies. Lauren’s previous research has looked at “earworms”, songs that get stuck in your head. But we discovered surprisingly little research on babies’ musical preferences. This was encouraging as it meant this was a worthwhile project from a scientific point of view.

The next step was to find the right composer: Grammy-award winner Imogen Heap. Imogen is a highly tech-savvy musician who just happened to have an 18-month-old daughter of her own. She was also intrigued by the challenges of the project. Few musicians had taken on the task of writing real music to excite babies while still appealing to parents. Musician Michael Janisch recorded a whole album of Jazz for Babies, but that was very slow and designed to soothe babies. Most music written specifically for babies sounds frankly deranged.

We met with Heap and gave her a set of recommendations based on what we had discovered from the past research. The song ought to be in an major key with a simple and repetitive main melody with musical devices like drum rolls, key changes and rising pitch glides to provide opportunities for anticipation and surprise. Because babies’ heart rates are much faster than ours so the music ought to be more uptempo than we would expect. And finally, it should have an energetic female vocal, ideally recorded in the presence of an actual baby.

Setting up the experiment

Fortunately Heap had her daughter, Scout, to help her with the composition. Heap created four melodies for us to test in the lab, two fast and two slow ones. For each of these she created a version with and without simple sung lyrics. Some 26 babies between six and 12 months then came to our lab with their mums and a few dads to give us their opinion. Amazingly most of the parents and 20 out of 26 babies seemed to share a clear preference for one particular melody. In line with our predictions this was a faster melody. Even more amazingly, this was the tune that had started out as a little ditty made up by Scout.

We knew which song the mums liked because we could ask them. We also asked the parents to tell us what their babies preferred best, because they are the experts on their own babies. But we also filmed the babies’ responses and coded the videos for laughs, smiles and dancing.

Now that we had a winning melody, Heap needed to turn it into a full-length song and it needed to be funny (to a baby). The secret was to make it silly and make it social. Around 2,500 parents from the C&G baby club and Heapäs fan club voted on silly sounds that made their babies happy. The top ten sounds included “boo!” (66%), raspberries (57%), sneezing (51%), animal sounds (23%) and baby laughter (28%). We also know babies respond better to “plosive” vocal sounds like “pa” and “ba” compared to “sonorant” sounds like “la”. Heap very cleverly worked many of these elements into the song.

Next it needed to be something that parents could enjoy themselves and share with their children. Happiness is a shared emotion and the success of nursery rhymes is that they are interactive. Heap carefully crafted the lyrics to tell a joyous tale of how we love our little babies wherever we are – from the sky to the ocean, on a bike or on a rocket. The transport theme permitted lots of plosives “beep, beep” and bouncing actions.

Our baby music consultants came back to the lab and listened to two slightly different sketches of the full song. This time we found that slightly slower seemed to work better (163 vs 168 beats per minute). Perhaps because it gave parents and babies a little more time to respond to the lyrics. We also found that the chorus was the most effective part of the song and determined which lyrics and sound effects worked better or worse.

After one final round of tweaks from Heap, we went for a different kind of test. We assembled about 20 of the babies in one room and played them the song all together. If you ever met an excited toddler or young baby, you will know that two and a half minutes is a long time to hold the attention of even one child, let alone two dozen. When The Happy Song played we were met by a sea of entranced little faces. This final bit wasn’t the most scientific as tests go but it definitely convinced me that we had a hit on our hands.

Now that we have a song that is both new and highly baby friendly, Lauren and I have a range of follow-up studies planned. We are planning to use the song in a range of experiments looking at how parents introduce their babies to music and hope to look more in depth at babies’ physiological responses to happy music.

This article originally appeared in the Conversation, Feb 2017

https://theconversation.com/we-created-a-song-that-makes-babies-happy-72309

Music to make babies laugh

How two psychologists and an army of babies helped Grammy winner Imogen Heap to write her new happy song for babies.

Being a new parent is an emotional rollercoaster. It is an even wilder ride for a baby. Baby experts often focus on coping with lows. As someone who studies infant psychology I think the highs are no less interesting. So for the last four years I’ve been researching baby laughter. Can I guarantee to make a baby laugh? Well, I’ve been working on it.

I conducted a survey of parents all over the world and have run various studies in the lab. I’ve come to see infant laughter as the flipside to all those tears. Crying and laughter are both social signals that let babies communicate with us. Crying is a signal of frustration and discomfort, laughter signals success and satisfaction. Laughs accompany each tiny triumph and each little “Eureka!”. This makes infant laughter a wonderful window into infant learning. In fact, laughter may be a tool babies use to learn about the social world.

It’s clear that a crying baby needs your help. What is less obvious is that a laughing baby is rewarding your assistance and holding your attention in order to learn from you. The biggest mystery in anyone’s life is other people. This is even more true for babies. They crave quality interactions with adults. Laughter is their secret weapon to get it. This is why laughing babies pull in hundreds of millions of views on YouTube. It also why one of the best ways to make a baby laugh is to take her seriously.

Now, if only more people would take this research seriously I might have funding to do it. Fortunately, last year I started a new job at Goldsmiths, University of London; a place with a reputation for encouraging radical ideas and creative approaches to research. (I always suspect that having blue hair may have helped me get the job.)

Shortly after I arrived I gave a talk to my new department about my research. Straight after the talk Prof. Lauren Stewart came up to me and suggested we collaborate on something. Lauren is a professor of the psychology of music and was interested in how babies respond to music. Music is laden with emotion and so it would be fascinating to learn more about its effect on young babies. I readily agreed but couldn’t find a suitable project.

Then by weird and happy coincidence in April last year C&G baby club called Lauren up saying they wanted help to create ‘a song scientifically proven to make babies happy’. At first we were wary. Brands have a fairly poor track record when it comes to using science. However, I had previously had a very positive experience doing research funded by Pampers. I had seen that baby brands cannot afford to lose their credibility and so have to be assiduous in what they do and what they claim. We met with C&G baby club to discuss their intentions. Our first proviso was that they shouldn’t use the word ‘prove’. Our second was that they had let us do real science. They readily agreed.

Once these ground rules were established the first step was to discover what was already known about the sounds and music that might make babies happy. We had some experience. My previous work on the Baby Laughter project had asked parents about the nursery rhymes and silly sounds that appealed to babies. Lauren’s previous research has looked at ‘earworms’, songs that get stuck in your head. We discovered surprisingly little research on babies’ musical preferences. This was encouraging as it meant this was a worthwhile project from a scientific point of view.

The next step was to find the right composer. With the help of FELT music consultancy, Grammy winner Imogen Heap was recruited as the composer. Imogen is a highly tech-savvy musician who just happened to have an 18 month old daughter of her own. She was intrigued by the challenges of the project. Few musicians had taken on the challenge of writing real music to excite babies while still appealing to parents. Musician Michael Janisch recorded a whole album of Jazz for Babies, but that was very slow and designed to soothe babies. Most music written specifically for babies sounds frankly deranged.

Plenty of research has looked at adults’ emotional response to music (such as the recent brain imaging study of Tinie Tempah). Research with babies is more piecemeal and eclectic, perhaps reflecting the difficulty of asking them what they like. Researchers know that babies can hear and remember music even while they are still in the womb and one curious study from 2000 found that newborn babies prefer Bach to Aerosmith. Most systematic work has been conducted by Laurel Trainor at McMaster University and her colleagues. She has found young babies have clear preferences for consonance over dissonance and can remember the tempo and timbre of music they’ve heard before. Babies prefer the female voice but like it even more when it takes on the high-energy sing-song tone of ‘motherese’. More accurately known as ‘Infant Directed Speech’ as it is a style we all naturally adopt when talking to babies.

We met with Imogen and gave her a set of recommendations based on what we had discovered.The song ought to be in an major key with a simple and repetitive main melody with musical devices like drum rolls, key changes and rising pitch glides to provide opportunities for anticipation and surprise. Because babies’ heart rates are much faster than ours so the music ought to be more up-tempo than we would expect. And finally, it should have an energetic female vocal, ideally recorded in the presence of an actual baby.

Fortunately Imogen had her daughter, Scout, to help her with the composition. Imogen created 4 melodies for us to test in the lab, 2 fast and 2 slow ones. For each of these she created a version with and without simple sung lyrics. Twenty-six babies between 6 and 12 months came to our lab with their mums and dads to give us their opinion on these 8 short pieces of music. Amazingly most of the parents and 20 out of 26 babies seemed to share a clear preference for one particular melody. In line with our predictions this was a faster melody. Even more amazingly, this is was the tune that had started out as a little ditty made up by Scout.

We knew which song the parents liked because we could ask them. We also asked the parents to tell us what their babies preferred best, because they are the experts on their own babies. But we also filmed the babies’ responses and coded the videos for laughs, smiles and dancing. We tried measuring changes in the babies’ heart rates and using a motion capture system to see if they were moving in time with the music. Unfortunately, this hit quite a few technical difficulties and there wasn’t time to solve the problems on our very tight schedule. This was worthwhile as pilot work and will be a really interesting area for future research.

But now we had a winning melody, Imogen needed to turn it into a full length song and it needed to be funny (to a baby). The secret was to make it silly and make it social. Around 2500 parents from the C&G baby club and Imogen’s fan club voted on silly sounds that made their babies happy. The top 10 sounds included “Boo!” (66%), raspberries (57%), sneezing (51%), animal sounds (23%) and baby laughter (28%). We also know babies respond better to plosive vocal sounds like “pa” and “ba” compared to sonorant sounds like “la”. Imogen very cleverly worked many of these elements into the song.

Next it needed to be something that parents could enjoy themselves and share with their children. Happiness is a shared emotion and the success of nursery rhymes is that they are interactive. Imogen carefully crafted the lyrics to tell a joyous tale of how we love our little babies wherever we are — from the sky to the ocean, on a bike or on a rocket. The transport theme permitted lots of plosives “Beep, beep” and bouncing actions.

Our baby music consultants came back to the lab and listened to two slightly different sketches of the full song. This time we found that slightly slower seemed to work better (163 vs 168 beats per minute). Perhaps because it gave parents and babies a little more time to respond to the lyrics. We also found that the chorus was the most effective part of the song and determined which lyrics and sound effects worked better or worse.

After one final round of tweaks from Imogen, we went for a different kind of test. We assembled about 20 of the babies in one room and played them the song all together. It was perhaps a silly thing to do but as Imogen and I sat on the sofa in front of a colourful and chaotic room full of parents and babies and pressed play we were cautiously optimistic. If you ever met an excited toddler or young baby, you will know that 2 ½ minutes is a long time to hold the attention of even one child, let alone two dozen. When The Happy Song played we were met by a sea of entranced little faces. This certainly wasn’t very scientific as tests go but it definitely convinced me that we had a hit on our hands. You can hear the song here. Please tweet me (@czzpr) and let us know if it makes your little ones happy too.

Thanks to all the mums, dads and babies who helped with the project. We couldn’t have done it without our small army of tiny music consultants. Nor without my two assistants Omer and Kaveesha who came to us through the excellent Nuffield Brilliant Club which arranges internships for A-level student in real working science labs. It was a frantic summer but we are very happy with the final song. You see a short video about the process here:

Now that we have a song that both novel and highly baby friendly, Lauren and I have a range of follow up studies planned. We are planning to use the song in a range of experiments looking at how mothers introduce their babies to music and hope to look properly at babies physiological responses to happy music. Meanwhile, I am finishing a popular science book called the Laughing Baby. It is all about how to make babies happy and why that is so important. You can preorder your copy here https://unbound.com/books/the-laughing-baby

Caspar Addyman is a Lecturer in Psychology, Goldsmiths, University of London. He previously spent 10 years working at Birkbeck Babylab. Caspar is a specialist in baby psychology with a particular interest in positive emotions in infancy. His book The Laughing Baby is published by Unbound in April 2020.

12 lessons in happiness you can learn from laughing babies

Morning Gloryville make people all over the world happy with morning raving. I wrote them a guest blog post about happy babies. This is it.

My job is to study baby laughter. (Yes, really!) I want to understand how babies cope with life. Arriving totally unprepared in a completely alien world is overwhelming. If you couldn’t laugh, you’d cry. And true enough babies do cry a lot. But they also laugh far more than we do and this is under-appreciated.

At some level, those laughs are signs of triumph. In a few short years babies teach themselves a huge range of incredible skills. But babies’ laughs and happiness are also about their connections with their loved ones. That’s why I started studying baby laughter and I think there are plenty of lessons there for all of us.

- Babies wake up happy. I’ve no idea why but they do. Last summer I went to Brazil to work with Pampers. We learned to our surprise that babies almost always start their day in good mood. Since I’ve discovered this I try to start my own day cheerfully, it seems to help. But I probably don’t need tell this to the Morning Glory crew.

- Babies give everything a go. Eleanor Roosevelt recommended doing one thing every day that scares you. Babies might seem like little scaredy kittens but they’re driven by incredible curiosity. They delight in learning new things. If you are a baby, every new day brings a new skill to master. And each success brings great happiness.

- Challenge yourself. If you are not a baby, finding new challenges can be more… challenging. But it will be worth it. Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi studied remarkably happy people from all walks of life and discovered that this was their secret.

- A person’s a person no matter how small. I recently helped Sarah Argent and Polka Theatre make a play about baby science for an audience of babies. We only managed to do this by treating them as little people. Being condescending does not work with babies, so it’s not going to work on anyone bigger.

- Babies give everyone a chance. A baby can melt any heart. Londoners will all have been there. You are on a bus with an irredeemably grumpy old man But then he starts pulling silly faces at a baby that’s peering at him over mum’s shoulder. That baby accepted him and that’s all it took.

- Music is magic. I spent the summer in Goldsmiths Infantlab helping Imogen Heap create music scientifically designed to make babies happy. We think we succeeded. Find a baby and play them the Happy Song and see if they agree.

- Hugs are drugs — A simple hug can make things better. It is doing so at a chemical level. Touch is our first sense to develop and the power of a mother’s touch to regulate stress has deep evolutionary roots.

- Consent matters — The best way to make a baby laugh is tickling but it’s only works if the baby trusts you and you have the baby’s permission.

- Connect — After tickles, peekaboo is the other universal game we play with babies. It is all about human connection. You have really tune into the baby to make the game work. And when you do you are rewarded with their delight.

- Really connect. They are pleased because you took time to interact with them. This lets them learn from you. And you will feel the intensity of their gaze. That is why the best way to make a baby laugh is to take her seriously.

- Live, love, laugh. Everyone loves babies and babies love everyone. Laughter and happiness are best when shared. We laugh with our friends. The bond between baby and parent is the best friendship there is and that’s why babies and parents laugh more than the rest of us. But everyone can improve their happiness by improving their relationships.

- Be present — Babies are little zen masters. Babies laugh more than us because they are constantly stopping to look around. They are never in a such a rush to get somewhere else that they miss the magic of right now.When you are happy make the most of it. Enjoy life, you will be glad you did.

Dr Caspar Addyman

Goldsmiths, University of London

For more like this, please look out for my book The Laughing Baby. It is being crowdfunded by Unbound Books. So it needs your support to make it a reality. Please pre-order your copy or tell your friends with babies

When I ran my survey of baby laughter over a thousand parents responded and nearly a hundred sent in videos. I have enough laughing babies to fill a book. So that’s what I am doing..

The Laughing Baby book is about the science of infant learning and why happiness matters right from the start of life. How do babies learn all those amazing skills completely from scratch and why do they have such a great time doing it? In four years of studying laughing babies, I’ve learned that laughter and smiles are of central importance at the start of life. Squeals of joy accompany all of a baby’s little breakthroughs. Laughs and smiles connect them to their nearest and dearest. It is how they reward you for the things they learn from you. If a baby is laughing, you can guarantee that they have just learned a new skill or else they want your help to do so. The book tracks all the essential skills a baby learns in the first two years from my perspective as baby psychologist. The book is being published by Unbound Books. They are an innovative company who crowdfund new books. Readers support the books they’d like to read and these get published. We need 600 people to pre-order the Laughing Baby to guarantee it is published. Here’s what you can to do help:

- Pledge your support for the Laughing Baby at Unbound.

- Like and share the Laughing Baby Facebook page.

- Share this page with anyone who thinks babies are awesome.

- Follow me on Twitter:

Do you like laughing babies? Of course you do, you’re not a monster. Then you’ll like my book The #LaughingBaby https://t.co/pTlxgqSVkE

— Caspar Addyman (@czzpr) October 15, 2016

Thank you, Caspar

Laughter makes the impossible possible. Just ask a baby.

Laughter makes life worth living. It makes impossible situations possible. Just ask a baby. Imagine the scenario; You have just been dropped on a completely alien planet. You know nothing about this place, about its people or its language, its customs or its culture, its animals or its architecture. Heck, even its very physics is alien to you. If you couldn’t laugh, you’d cry. This the world of a baby.

But for a baby it’s even worse than that. Not only have you arrived cold, wet and helpless in a world you know nothing about, in fact, you know nothing about anything. Your memory is blank. Your limbs are not yours to command. Your muscles are too feeble to even lift your head. You can’t control your most basic bodily functions. You don’t even have a language of your own to think in. Oh, and did I mention all those aliens about fifteen to twenty times your size? No wonder babies start screaming shortly after their arrival.

The first month or so is a time of bewilderment, mostly taken up with sleep and screaming, nutrition and growth. But three cheerful miracles help babies survive in this terrifying situation. Survive and indeed thrive. First, babies come equipped with the most remarkable computers ever invented. Babies brains are the most powerful learning devices in the known universe. In two short years babies probably learn more profound truths than in the rest of lives. Secondly, babies have landed in an extremely benign environment. Human parents do infinitely more for their offspring than any other species. People have an inbuilt tendency to cherish and support babies. We can’t help loving these new invaders into our lives. Thirdly and most remarkable of all, it turns out we can communicate with each other right from the start. Despite no shared language or culture we can make an amazing emotional connection from day one.

For more like this, please look out for my book The Laughing Baby. It is being published by crowd-funded publisher, Unbound Books. So it needs your support to make it a reality. Please pre-order your copy or tell your friends with babies 🙂

https://unbound.com/books/the-laughing-baby

But by weird and happy coincidence in April this year C&G Baby Club called Lauren up saying they wanted her help to make ‘scientifically proven happy song for babies’. Lauren called me and, of course, we said yes. With help of FELT music consultancy, they recruited Grammy winner Imogen Heap as the composer and Michael J Ferns and Pretzel Films to film it.

It was a frantic summer but we are very happy with the final song. And while the song is great but you should start by watching the Making of.. video.

Ready?

Thanks to all the mums, dads and babies who helped with the project. We couldn’t have done it with our small army of tiny music consultants.

Please let us know if it makes your little ones happy too.

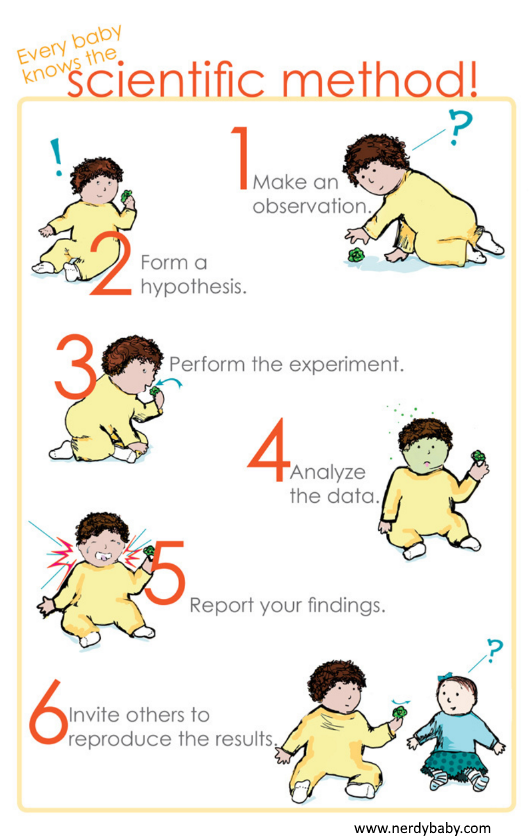

http://www.nerdybaby.com/every-baby-knows-the-scientific-method-mini-poster-11×17 I

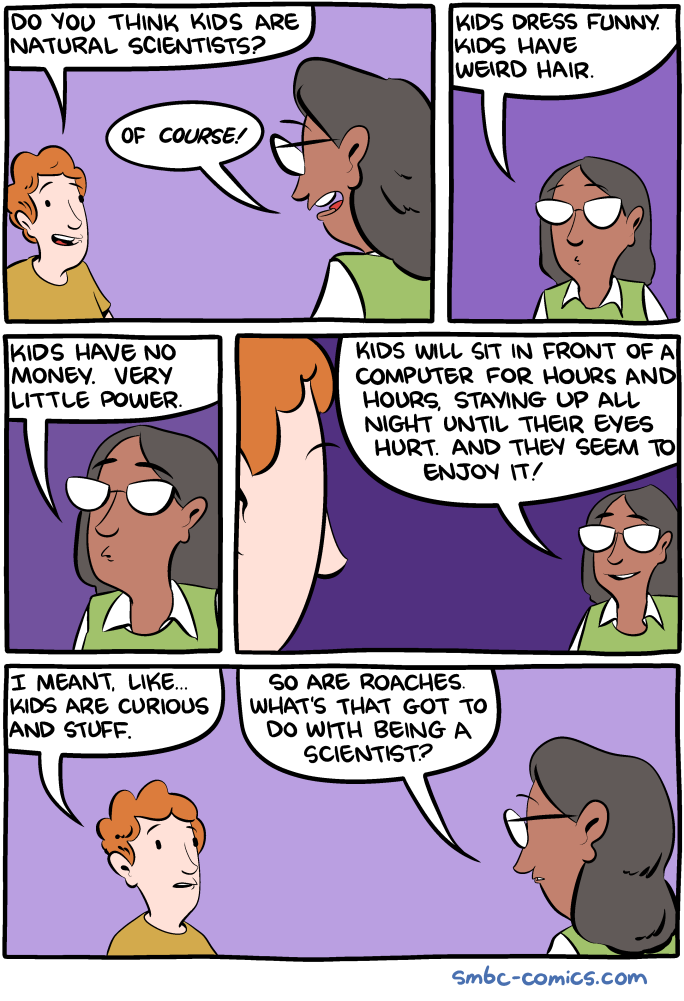

Source: Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal – Natural Scientists

How to take your first steps in baby science or baby theatre

Imagine for a moment that you wanted create a piece of theatre to entertain babies or a scientific experiment to test their understanding, how would you go about it? In this article I will give you a handy six step recipe that will help you get started in either situation. And along the way I hope to persuade you why these are both such worthwhile and important undertakings. The surprising thing is that the process is very similar. Despite 10 years of experience running experiments with babies I only discovered this myself very recently.

Over the last few months myself and colleagues from Birkbeck Babylab have been collaborating with the creative team at Polka Theatre. The goal has been to make a piece of theatre for 6 to 18 month old infants based on our research as part of Polka’s upcoming Brain Waves Festival (21 Sept — 2 Oct 2016). Brain Waves is a two-week long festival of science and theatre that matches artists and neuroscientists to create new theatre productions for children. Supported by a Wellcome Trust People Award the festival features four original works for a range of audiences between 6 months and 16 years old.

To create a show for babies, Polka turned to Sarah Argent, a very experienced theatre director, who in recent years has specialised in creating works for babies and toddlers. In February, Sarah came to Birkbeck Babylab and after speaking to a range of our colleagues she honed in on me and my fellow baby scientists Sinead Rocha and Rosy Edey. Rosy studies how we read the social movements of others. Sinead investigates rhythm and dance in babies and I study what makes babies laugh. Dancing babies, social babies, laughing babies. We could see how that makes a good start for a show. Sinead and I have also spent several years studying babies’ sense of time. We were curious how Sarah and her team would work with that.

In fact, at that first meeting, we were very curious about everything…

Step zero: Why are we here?

Let’s take a step back, why would you want to create theatre for babies or try to run a psychology study with infant participants? Wouldn’t theatre for babies be limited? Wouldn’t experiments with adults give you clearer answers?

One important first principle that seems to be shared by baby psychologists and baby theatre makers is that we both treat babies as full citizens. Theatre for babies is not theatre for adults but smaller. And science for babies is not science for adults but simpler. Baby psychologists are not simply cataloguing when various abilities come online. For us, babyhood is not merely a way-station to something better. We care about what it is like to be a baby. We try to understand babies from the inside. In theatre for babies, the ambitions seem to be the same.

Step one: Why are we here, today?

Our lofty ambitions and elaborate, theory won’t mean a thing to the babies. To communicate with them we have to be concrete and we have to be focused. We must always start with a very specific question. To get answers from them we must present them with just one thing at a time.

Sarah’s previous show for babies Scrunch is a great example of this. Developed from her first show, Out of the Blue, performed at Polka at various times between 2008 and 2014, Scrunch is set at Christmas and it features just one actor (Sarah’s husband Kevin Lewis). It builds slowly and smoothly, transitioning from event to event at a pace that is often determined by the babies in the audience. Parents coming to our lab are often surprised by how short the actual experiments are. Their baby may spend as little as 3 or 4 minutes doing the task we set them. To get that exactly right, you need to think deeply about your goals before you set off. You must consider lots of possible options to find the best way to ask your question.

I think this is somewhere that baby science can learn from baby theatre. In my experience people in science are impatient problem solvers. You start telling them about something and they leap ahead of you second guessing outcomes and jumping to conclusions, the tempo seems very different in theatre. Our first full day of collaboration at Polka, the whole creative team assembled with Rosy, Sinead and I to discuss our work and there was no rush. People work in theatre are a good audience. They really do listen. They absorb, then they ask great questions.

Step two: Who is our audience?

A six-month-old is a very different person from a sixteen month old. A hungry baby is different person from the same baby after a good meal. An overtired toddler can have a lot of angry energy. We have to work with this not against it.

We never expect any given baby to “pass or fail” and results are based on the group not the individual because we might not get a baby at their best. For similar reasons, we rarely attempt to track the development of babies over time, preferring to test a group of 6 month olds and compare them to different groups of 4 or 8 month olds.

We try to make our tasks work with a wide age range. But often babies have other ideas. Sinead and I tried to teach babies about time by playing a game. Seven times in a row, Sinead would lift the babies’ hands every 4 seconds. On the eight time, she’d sit there and see if the babies anticipated. Four, six & eight month olds played the game happily. You can see a video of this here. But from 10 months and up, babies refused to even let us hold their hands. For them a different game would be required. In baby theatre, there isn’t the luxury of having a narrow age range. The show must have broad appeal.

Babies are fantastic participants for psychological studies because they are both open-minded and honest. They will consider anything we present them with but they won’t hold back their opinions. This makes them challenge but rewarding audience for theatre.

Step three: The story

I read somewhere that good storytelling is about being simple, truthful, emotional, real and relevant. This would make for a good infant experiment too. An ideal for infant scientists would be to observe babies solving problems in their everyday lives. We can rarely do this but our lab must recreate as much of a natural situation as possible.

And it must be engaging. Infant attention is a precious commodity. After a few minutes in one situation their attention will wander. Everything is interesting to a baby. I’ve lost count of the number of times a baby has found his or her socks more interesting than my experiment. I am very envious when I see Sarah’s shows keeping babies entranced for 20 minutes or more. If I can learn some of her tricks this collaboration will have been invaluable to me.

The final rule is “show, don’t tell.” With preverbal infants, this goes without saying.

Step four: Rehearsal

Despite all the handy rules of step three, the mantra for step four is “easier said than done.” Nothing will work quite as you expect and solving problems is the order of the day. Early rehearsals (or piloting as we call it) are where the real creativity happens.

Sarah very wisely invites some babies to those early meetings because as we know well from our BabyLab, no battle plan survives contact with the enemy. In one experiment we had a ball on a stick that swung round for the babies to grab. They greatly enjoyed it. The trouble was they wouldn’t let go. It took a great deal of practice to learn how to distract the babies in just the right way it that wouldn’t provoke a rebellion.

When you get to the actual performance so much is happening at once that you need to have had extensive practice. Technical and dress rehearsal are invaluable in baby science too. In our studies there is often someone hiding behind a curtain jingling bells to get babies looking in the right direction madly pressing buttons to make teddy bears pop up on screen at just the right time and to ensure all the data gets recorded.

Step five: Showtime

In a recent ‘manifesto’ on theatre for children, Purni Morrell declared that “Art has to start from a shared position of ignorance.” This holds true for science too. You can’t make up your mind in advance. Or what would be the point?

And this all goes double when you are working with babies. Babies are enigmatic. If you think you know what baby is thinking you are probably wrong. Until we are there on the day with the babies we can’t know what will happen.

I do know that I am really looking forward to the premiere of Shake, Rattle and Roll.

As part of Brain Waves Festival we are running a series of blogs about making theatre with neuroscientists. If you have any questions or want to let us know what you thought, you can do on social media using #BrainWavesFest

Original post: How to take your first steps in baby science or baby theatre (Polka blog)

Dr. Caspar Addyman is a Psychology Lecturer at Goldsmiths, University of London. He is a developmental psychologist interested in learning, laughter and behaviour change. The majority of his research is with babies. He has investigated how we acquire our first concepts, the statistical processes that help us get started with learning language and where our sense of time comes from. Before moving to Goldsmiths, he spent 10 years working in Birkbeck Babylab.